Introduction: The Silent Architects of Power

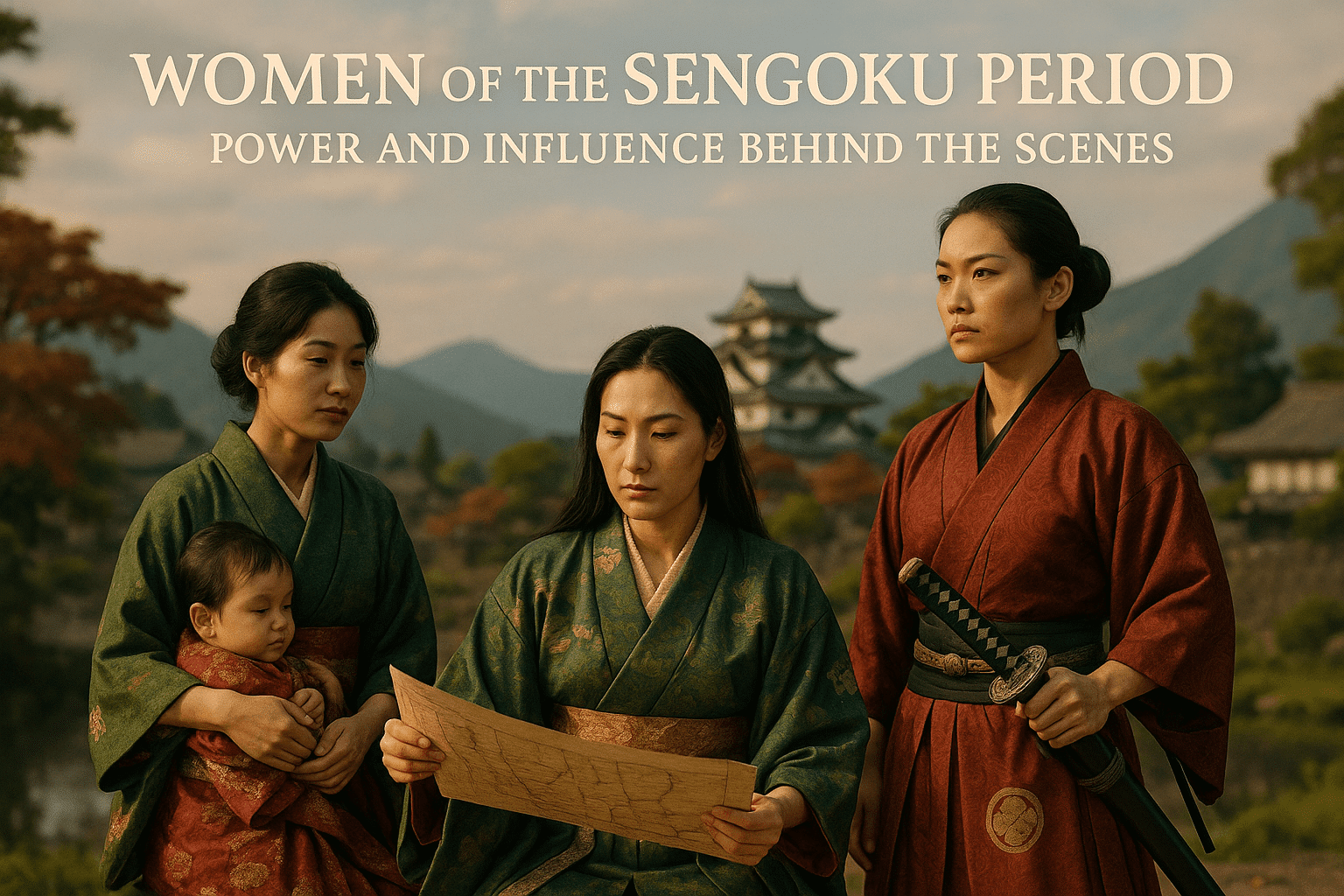

Amid the chaos of civil war, shifting alliances, and relentless ambition, the Sengoku period (1467–1615) stands out as one of the most turbulent eras in Japanese history. Also known as the Warring States period, it was an age dominated by powerful daimyōs, legendary battles, and political upheaval. Yet behind the clamor of swords and the rise and fall of great men were the silent architects of power—women whose influence ran deep beneath the surface.

Too often, narratives of this era focus solely on the battlefield and the men who fought upon it. But threaded through family negotiations, castle intrigues, spiritual guidance, and even direct governance, women shaped the social and political fabric of feudal Japan in profound ways. Whether as wives, mothers, strategists, or consorts, their impact was subtle yet enduring—etched not in chronicles of war, but in the legacies of clans that survived the storm.

This article seeks to shine light on these overlooked figures—women who wielded influence not with armies, but with wisdom, resilience, and quiet authority.

Women in a Warrior’s World: Context and Custom

In the violent and chaotic world of Japan’s Sengoku period (c. 1467–1600), warfare and political upheaval redefined every corner of society—including the roles and expectations of women. While samurai culture was undeniably patriarchal, with men holding power both on and off the battlefield, women were far from absent in shaping their households, clans, and even national politics.

Culturally, Sengoku-era women were guided by Confucian and Buddhist ideals that emphasized obedience, chastity, and loyalty. These tenets were ingrained from a young age through family teachings and texts like “Onna Daigaku” (Great Learning for Women), which outlined their expected duties as daughters, wives, and mothers. Yet beneath these strict social codes, women often exercised quiet yet formidable influence.

Marriage for high-ranking women was less a personal union and more a political alliance. Daughters of daimyo (feudal lords) were frequently used to cement bonds between rival factions or secure peace between warring clans. Once married, women were expected to manage estates, oversee servants, and uphold the honor of their husbands’ households—duties that required intelligence, diplomacy, and resolve.

Legally, their rights were limited. Property ownership often passed through male lines, and inheritance typically favored sons. However, widows or women acting as regents for underage heirs could wield considerable authority. Legal standing was flexible in times of crisis, revealing a society that, while ideologically rigid, was pragmatically adaptive.

Though women were officially excluded from battlefields, custom did not always reflect reality. Women of the bushi class trained in self-defense, and in times of siege or clan collapse, many took up arms to defend their homes. This blurred the lines between submission and strength, showing that their roles, while constrained, were never static.

Ultimately, within the hierarchical and demanding world of Sengoku Japan, society expected women to be loyal, discreet, and supportive. But history reveals a different picture: one of resilience, adaptability, and often-unseen power behind the armor-clad men.

Mothers of Daimyō: Bloodlines and Legacy

In the volatile world of the Sengoku period, bloodlines weren’t just symbols of prestige—they were tools of survival and dominance. Mothers of daimyō, often born into powerful samurai or aristocratic families, played critical roles in reinforcing clan legitimacy, securing alliances, and perpetuating political influence through their children. These women were strategically wed to forge bonds between factions, their marriages carefully negotiated as weapons of diplomacy in a fractured land.

Producing a legitimate heir was only the beginning. A mother’s lineage could elevate a child’s claim to leadership or tip the balance in succession disputes. Many women used their natal clan’s influence to advocate for their sons, ensuring their rise within the volatile hierarchy of samurai rule. In cases where internal rivalries threatened stability, mothers often served as mediators, leveraging their familial connections to broker peace or secure power-sharing agreements.

Some stood out not just as bearers of heirs, but as architects of dynastic legacy. The likes of Lady Oai, mother of Tokugawa Hidetada, and Lady Tsukiyama, wife to Tokugawa Ieyasu, infused their offspring with not only noble blood but political leverage. Their backgrounds brought valuable allies into the Tokugawa circle, solidifying the base from which the shogunate would eventually rise.

Through strategic marriages, careful management of succession, and their ability to preserve or reshape powerful bloodlines, the mothers of Sengoku daimyō quietly shaped the future of Japan—not with swords or armies, but with legacy.

Wives and Strategists: Political Partnerships

In the chaos of the Sengoku period, where allegiances shifted and battles reshaped Japan’s political landscape, samurai and daimyō wives were far more than passive observers. These women wielded influence behind the scenes, acting as trusted advisors, tacticians, and diplomatic envoys. Their deep understanding of clan politics and regional dynamics made them indispensable partners in both wartime strategy and peacetime governance.

Wives like Nene, consort of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, were known to manage courtly relations and smooth factional tensions, often serving as the interpersonal glue that bound volatile alliances. Others, such as Lady Yamauchi Chiyo, navigated espionage and diplomacy, keeping their clans informed and secure. These women often managed castle affairs, oversaw resource distribution, and even directed troop movements when their husbands were away at battle.

They also facilitated political marriages, negotiated hostages, and corresponded with rival clans to broker peace or strengthen positions. Their learning in cultural and martial arts equipped them for these tasks, allowing them to interact effectively with male leaders and religious figures alike.

Far from being confined to domestic roles, Sengoku wives were integral to the political calculus of their time—shrewd, resourceful, and often the unseen minds behind strategic decisions that shaped the fates of clans.

Onna-Bugeisha: Warriors in Their Own Right

Among the many shadows of the Sengoku period’s war-torn landscape stood a distinct group of women who did not confine themselves to palaces or passive roles—these were the Onna-bugeisha, female warriors who trained in battlefield arts and upheld the honor of their clans with both sword and strategy. Contrary to the common perception of samurai warfare as a male-dominated sphere, these women stood as defenders of their homes, fortresses, and even territories, often when male leadership was absent.

Figures like Tomoe Gozen—though more associated with the earlier Genpei War—inspired generations of women to master the naginata, the traditional polearm associated with female warriors. In the Sengoku era, women such as Nakano Takeko emerged, leading troops and dying in battle with valor comparable to their male counterparts. These women weren’t merely anomalies; they represented a persistent facet of samurai society that challenged the rigid expectations of gender roles.

Their participation in combat was often born out of necessity, but it was also rooted in a cultural ethos that revered loyalty, bravery, and the defense of one’s household. Whether stationed in castles under siege or riding into battle, Onna-bugeisha asserted an agency that history too often overlooks. Their martial prowess wasn’t just symbolic—they were real forces in regional conflicts, showing that power during the Sengoku period could be wielded just as fiercely from a woman’s hand.

Behind Paper Screens: Intelligence and Espionage

While samurai warlords clashed on fields soaked with ambition, behind sliding paper screens, women operated in shadows—decoding secrets, orchestrating deceptions, and manipulating the flow of information with elegance and precision. Far from passive bystanders, they wielded intelligence as deftly as blades.

Elite women, especially from samurai families, were often trained not only in martial skills but in the subtle arts of observation, message delivery, and diplomatic maneuvering. Wives and concubines of daimyo had unique access to court politics and rival leaders, making them invaluable as informants. Their perceived roles as ornaments of the household gave them an advantage—few suspected them of acting as covert agents.

Some, like Mochizuki Chiyome, allegedly built entire networks of female spies disguised as shrine maidens and entertainers. These kunoichi infiltrated enemy strongholds, gathered intelligence, and sowed internal discord—all under the veil of innocence and piety. Through coded letters, concealed compartments, and the disciplined use of misinformation, these women became silent architects of wartime strategy.

They also safeguarded secrets closer to home. Loyal retainers and onna-bugeisha (female warriors) often protected their lords’ communications, providing double layers of loyalty and discretion. In times of siege or political upheaval, some women even used their positions to mislead enemies—setting false trails, or posing as messengers to deliver forged plans that influenced outcomes far beyond the walls they inhabited.

In the tangled webs of Sengoku politics, espionage was as potent as any blade—and many of its most skillful weavers were women.

Legacy and Echoes: Shadows on the Scroll

While warlords and samurai etched their names across the annals of Sengoku Japan, many of the women who wielded silent power were left in the margins, their stories whispered rather than written. Historical records of the era often relegated women’s roles to domestic or familial spheres, despite their political acumen and battlefield presence. Some, like Nene, wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, were memorialized for their virtue and loyalty—figures supporting the male narrative rather than independent agents of history. Others, like Yodo-dono, were alternately vilified or romanticized, their legacies distorted by the biases of chroniclers more interested in dynastic drama than nuanced truth.

Yet, echoes of their impact ripple through Japanese cultural memory. From theater and film to historical fiction and manga, Sengoku women have inspired reinterpretation, fueling a collective reimagining that grants them overdue agency. Their resilience and influence—once sidelined—now serve as powerful symbols of strategic intelligence, political resilience, and the complexities of legacy. As modern scholarship uncovers letters, artifacts, and overlooked chronicles, the shadows on the scroll begin to shift, allowing these women to step into the light of remembered history.

Conclusion: Strength Quietly Wielded

In the chaotic swirl of the Sengoku period, where swords clashed and allegiances shifted like wind-blown leaves, women moved quietly—yet decisively—through the currents of power. Far from passive figures, they were resilient strategists, trusted counselors, and unyielding guardians of family and clan. Whether negotiating high-stakes alliances, managing domains in their husbands’ absence, or influencing decisions from behind curtained screens, these women embodied a strength forged not with steel but with intellect, loyalty, and grace.

Their contributions often escaped the annals written by victors focused on battlefield glory, but their influence resonates through the families and legacies they helped preserve. Without a throne or a title, they shaped futures—and occasionally, the tides of war itself. In recognizing their quiet power, we gain a fuller, richer understanding of Sengoku Japan—not just as a world of warriors, but of women whose impact still echoes in the shadows of castles and the pages of history.