Introduction: Blades in a Modern Age

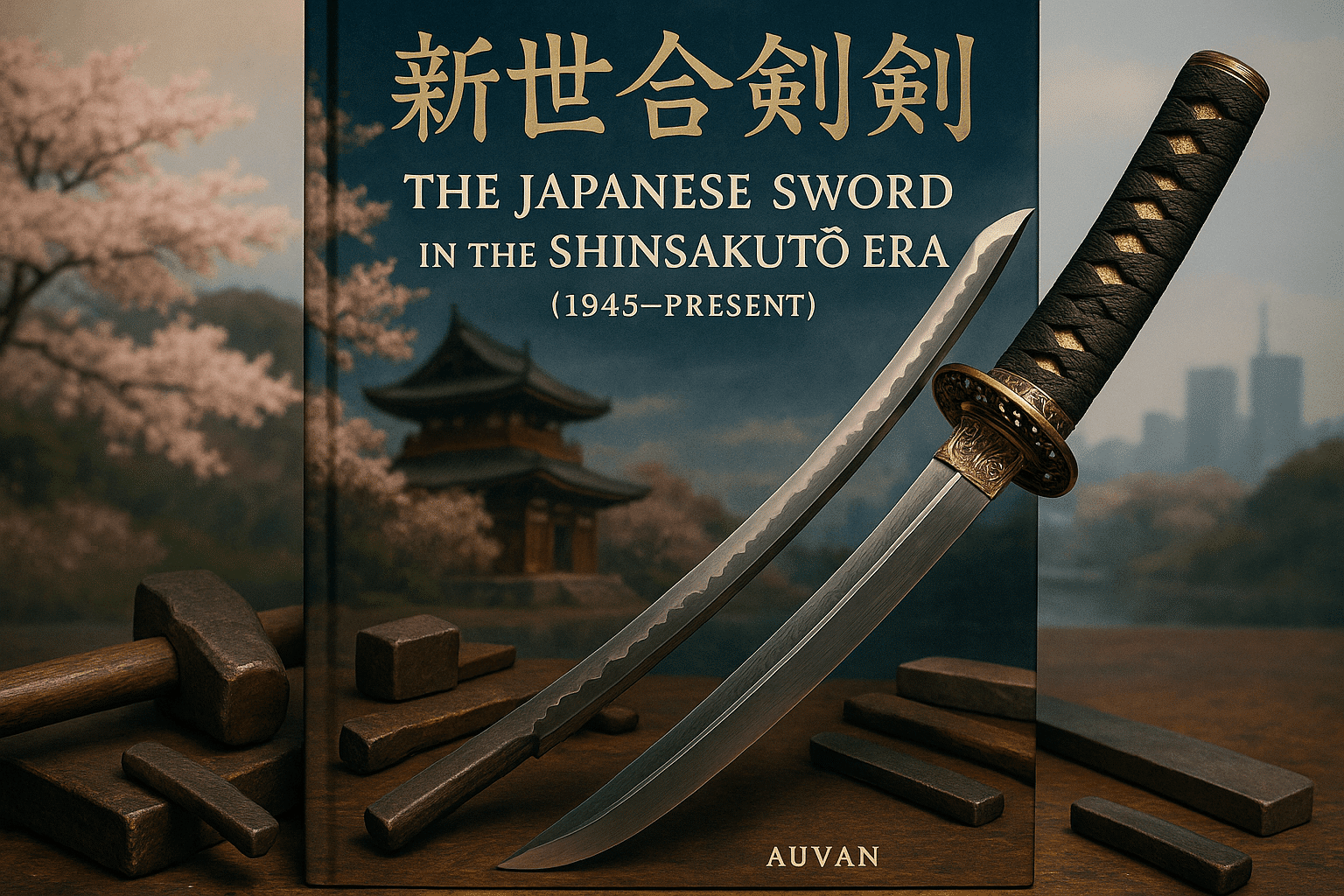

Even in an age defined by nuclear power and digital precision, the Japanese sword—nihontō—remains a powerful symbol of craftsmanship, tradition, and cultural identity. In the aftermath of World War II, as Japan underwent sweeping transformations socially, politically, and economically, the sword’s role evolved dramatically. Once a battlefield weapon and a samurai’s soul, the nihontō today occupies a complex space as both a revered art form and a bridge to Japan’s storied past.

The post-war period, known in swordmaking circles as the Shinsakutō era, marked a renaissance of sorts. Although the Allied Occupation initially restricted sword production, passionate artisans and collectors helped revive the craft—shifting its focus from function to form, from war tool to aesthetic object. Modern swordsmiths blend centuries-old forging techniques with contemporary sensibilities, breathing new energy into a tradition that might otherwise have faded into obscurity.

As we explore the Shinsakutō era, we’ll uncover how Japanese swords have transcended their martial roots to become emblems of resilience, continuity, and national pride in a rapidly modernizing world.

Defining the Shinsakutō Era

The Shinsakutō era, meaning “newly made swords,” refers to the period of Japanese sword-making that began in 1945 and continues to the present day. This era marks a dramatic shift from earlier historical periods such as the Kotō (ancient swords, pre-1596), Shintō (new swords, 1596–1781), and Shinshintō (new-new swords, 1781–1876), which were defined by their connection to the samurai class and their roles in warfare.

Following Japan’s defeat in World War II, sword-making was heavily restricted during the Allied Occupation, with many traditional craftsmen banned from forging blades. However, as Japan regained sovereignty, the art of sword-making was revived—but now within a vastly different cultural and legal framework. Post-war swordsmiths, working within the limitations of government regulation and a non-militarized society, turned their focus toward preserving the artistry and tradition of the nihontō as cultural treasures rather than weapons.

Unlike swords of earlier eras, Shinsakutō blades are typically crafted for ceremonial, artistic, or collector purposes. Many modern smiths rigorously study classical techniques and styles, seeking to emulate or reinterpret the masterpieces of the past while also infusing contemporary creativity. The result is a dynamic period of revival and innovation, where centuries-old craftsmanship adapts to modern contexts.

In essence, the Shinsakutō era is distinguished not only by its chronological place in history but also by its symbolic transformation—marking a pivot from swords as tools of war to revered expressions of cultural heritage.

Swordsmiths in a Time of Peace

With Japan’s defeat in World War II, the practical need for swords vanished almost overnight. The postwar era, marked by the U.S. occupation and sweeping demilitarization policies, imposed strict regulations on swordmaking. Swordsmiths who had once crafted weapons for soldiers and officers now faced an existential crisis: without war, what purpose did the sword serve?

Yet, rather than letting the tradition fade, many smiths saw this as a turning point—a chance to reframe their work not as warriors’ tools, but as objects of cultural and artistic significance. Rebuilding under these new parameters required not just technical skill, but also philosophical resolve. Swordsmiths began emphasizing craftsmanship, historical continuity, and aesthetics. The Japanese sword evolved from weapon to art object, a symbol of national heritage and discipline.

Master smiths like Miyairi Akihira and Gassan Sadakazu played instrumental roles in this transformation. Their workshops became not just forges, but sanctuaries of tradition, where each blade was imbued with reverence for the past and responsibility for the future. Protected under the Cultural Properties Protection Law and fostered by institutions like the NBTHK (Society for the Preservation of the Japanese Art Sword), swordsmithing persisted—not as an industry of war, but as a meticulous craft preserving the soul of the samurai era.

In this time of peace, the hammer ringing on steel no longer prepared a weapon for battle, but a work of enduring beauty and spirit.

Tradition Meets Regulation

In postwar Japan, swordmaking entered a paradoxical landscape where preserving tradition had to align with stringent modern regulations. The Act for Controlling the Possession of Firearms and Swords, enacted in 1958, fundamentally shaped the way contemporary swordsmiths operate. While the law restricts the ownership and manufacture of weapons, it carves out a critical exception for Japanese swords made using traditional methods, recognizing them as works of art rather than tools of war.

To legally produce swords, modern smiths must be licensed by the Agency for Cultural Affairs and are limited to crafting no more than 24 swords per year. This quota system both preserves quality standards and keeps production volumes in check, distinguishing these creations from mass-produced items. However, it also adds pressure to every blade forged—a sword must justify its existence within these narrow legal bounds.

Collectors and enthusiasts must also navigate these rules carefully. Swords must be registered with a special permit, and their ownership is strictly monitored. Still, these regulations haven’t stifled the art—instead, they’ve pushed it into new realms. Swordmakers today tread a delicate balance, innovating within tradition and responding to a society that values history, craftsmanship, and legality in equal measure. This legal framework has become part of the modern sword’s identity, binding the future of Nihontō craftsmanship to both heritage and state oversight.

The Spirit of the Shinsakutō

In the Shinsakutō era, the Japanese sword transcends its historical role as a weapon to become a vessel of spirit, heritage, and artistic expression. At the heart of contemporary sword-making lies a deepening reverence for tradition—not as a relic of the past, but as a living continuum. Modern swordsmiths see themselves as caretakers of a lineage that stretches back over a millennium, bearing not merely skills but a sacred responsibility.

This spirit is grounded in the principle of shokunin kishitsu—the artisan’s ethos of devotion, discipline, and humility. Each blade is the culmination of unspoken knowledge passed hand to hand, fire to forge, soul to steel. The process resists industrial shortcuts; it demands ritual precision, intuitive touch, and unwavering patience. In that crucible of effort, form and spirit merge.

While the sword no longer serves the battlefield, its spiritual significance endures. For many smiths, the act of forging becomes a meditation, a dialogue between human intent and natural forces. Earth, water, fire, and air all speak through the steel. This harmony of elements shapes not only the blade but the inner clarity of its maker.

Artistic expression in the Shinsakutō period also reflects a mindful restraint. Unlike flamboyant reinterpretations, many modern blades exhibit a quiet purity—elegant in line, subtle in curve, unyielding in purpose. Yet even as artisans honor tradition, they remain unique voices within that discipline, each sword a singular statement of balance between past and present.

Ultimately, the spirit of the Shinsakutō is one of reverent continuity—where innovation walks in step with inherited practice, and every sword becomes a silent yet eloquent testament to the enduring soul of Japanese craftsmanship.

Notable Modern Swordsmiths

The Shinsakutō era has witnessed a remarkable revival and preservation of traditional Japanese swordmaking, thanks to the artistry and dedication of modern swordsmiths. Among the most influential is Miyairi Akihira (1927–1993), a master smith who helped reestablish swordmaking after World War II. Trained under Kurihara Hikosaburo, Akihira became one of the first smiths to receive government recognition post-war, earning prestigious titles like Mukansa, awarded to those whose work no longer requires formal competition for exhibition inclusion. His swords, known for their balanced form and powerful hamon (temper lines), embody the spirit of classical craftsmanship blended with 20th-century revivalism.

Another towering figure is Gassan Sadatoshi, a living national treasure and torchbearer of the historic Gassan school, which dates back to the Kamakura period. His work maintains the signature ayasugi hada—a flowing wood grain pattern unique to his lineage—while pushing the boundaries of artistic expression within traditional constraints. Sadatoshi has played a pivotal role in training younger smiths and promoting nihontō as both art and cultural heritage in Japan and abroad.

These modern masters, along with others like Yoshindo Yoshihara and Sumitani Masamine, have ensured that despite changing times, the Japanese sword remains not just an artifact of the past but a living, evolving expression of craftsmanship. Their commitment to excellence and reverence for tradition continues to breathe life into the Shinsakutō era.

Living Art: The Sword Today

In the Shinsakutō era, the Japanese sword has undergone a profound metamorphosis. No longer forged for the battlefield, today’s swords are shaped by a blend of artistry, craftsmanship, and reverence for heritage. Modern smiths, often recognized as Living National Treasures, pursue the spirit of the blade with the same devotion as their ancestors—honoring centuries-old techniques while framing their work within a contemporary context.

Collectors, martial artists, and spiritual seekers alike now regard the katana not merely as an instrument of war, but as a vessel of the Japanese soul. In dojo and shrine ceremonies, swords are wielded not to harm, but to perfect character and embody precision and mindfulness. In galleries and national museums, they are displayed as sculptural icons representing a lineage of discipline, refinement, and national identity.

More than just the continuation of a tradition, the modern Japanese sword stands as a living art form. It connects the past to the present, carrying with it the echoes of samurai honor and artistic devotion. In each polished curve and forged hamon, the contemporary sword tells a timeless story—one of beauty born in fire, guided by purpose, and sustained by the human spirit.