Origins of the Hōjō Clan

The Hōjō clan emerged from modest beginnings as minor nobility in Izu Province. Their ancestral ties linked them to the influential Taira and Fujiwara families, granting them a fragile connection to the imperial court but affording little actual authority. It was Hōjō Tokimasa who changed the clan’s destiny. Amidst the turmoil of the Genpei War, Tokimasa allied with Minamoto no Yoritomo, a pivotal decision that set the stage for the Hōjō’s rise. Yoritomo, then a political exile in Izu, married Tokimasa’s daughter, Masako, forging a critical bond between the two families. This alliance helped elevate the Hōjō among the emerging samurai elite. By the time Yoritomo founded the Kamakura shogunate in 1192, the Hōjō had positioned themselves as discreet yet influential insiders, ready to step into the power vacuum that would soon emerge.

The Kamakura Shogunate and the Path to Power

After Yoritomo established the Kamakura shogunate, the Hōjō clan moved deliberately and quietly. Although Yoritomo held formal power as shogun, it was his wife’s family—the Hōjō—who were poised to guide the future of samurai rule. When Yoritomo died in 1199, his young son inherited leadership. In reality, true authority shifted to Hōjō Tokimasa, now shikken, or regent, a position newly created to consolidate control while maintaining the façade of Minamoto dominance. The Hōjō preferred to shape policy and administration from behind the curtains, placing child shoguns on the throne and guiding their reigns. Through shrewd appointments and purposeful marriages, the clan tightened their grip on the shogunate. They governed with restrained discipline, eschewing ostentation in favor of order and stability, securing their place as the unseen architects of Japanese rule.

Hōjō as Regents: Structure, Control, and Strategy

The Hōjō exercised authority as regents to the shogunate, a role that allowed them to shape the governance of Japan without ever claiming the title of shogun for themselves. This careful balance preserved the illusion of continuity while keeping true power securely in Hōjō hands. Central to their rule was the establishment of the Hyojōshū, or Council of State—a powerful assembly of military and legal experts that streamlined administration and solidified collective governance under Hōjō leadership. In 1232, the Hōjō codified rule through the Goseibai Shikimoku, a pioneering legal code that promoted fairness, precedent, and moral order over arbitrary decision-making. By resolving land disputes and clarifying samurai duties through structured law, the Hōjō not only curbed the ambitions of rival clans but also reinforced loyalty and stability. Their power stemmed not from brute force, but from an unyielding commitment to order and clarity; their legacy was one of calm, methodical control.

Defending the Realm: The Mongol Invasions

The greatest test of the Hōjō clan’s resolve came with the Mongol invasions. Twice—first in 1274 and again in 1281—Kublai Khan’s formidable fleets threatened Japan with overwhelming force and unfamiliar tactics. Understanding the gravity of the threat, the Hōjō acted swiftly. They called upon samurai from across the land, uniting erstwhile rivals for a single purpose. Under their leadership, the shores of Kyūshū were fortified with walls and watchtowers. Defense became a matter of collective discipline; every village and temple played a part. When the Mongol armies landed, they met organized resistance. The Japanese defense, coupled with fierce typhoons—the legendary kamikaze, or divine winds—repelled the invaders both times. The Hōjō, ever reserved, regarded survival not as luck but as duty fulfilled. Through their preparedness and unwavering focus, they preserved the realm in its hour of need.

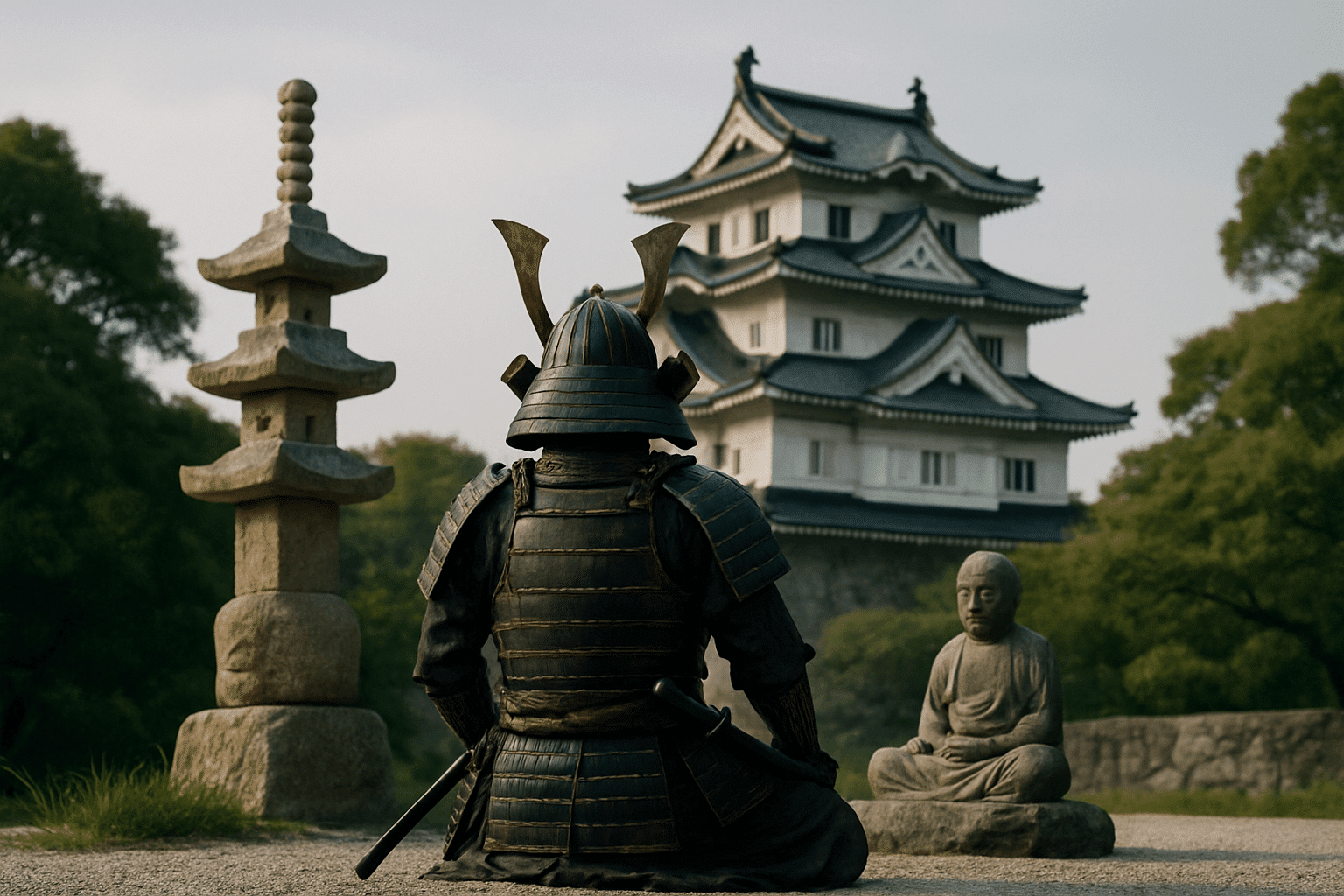

Cultural Influence and Quiet Power

Though the Hōjō clan wielded power from the shadows, their influence on Japanese culture during the Kamakura period was profound. They became quiet patrons of Zen Buddhism, whose disciplined austerity harmonized with samurai ideals. Under their support, temples blossomed as sanctuaries of serenity, drawing monks and teachings from China. The arts flourished in this atmosphere—ink painting, the tea ceremony, and a refined sense of beauty rooted in restraint took hold. The Hōjō guided not only the mechanisms of government but the spirit of their time, valuing simplicity over extravagance. Their presence fostered an environment where introspection, discipline, and understated elegance became the hallmarks of Kamakura culture.

Decline and the Fall of the Hōjō

The Hōjō clan’s dominion waned due to mounting internal discord and growing external threats. By the early 14th century, factionalism eroded their unity and undermined public confidence. The once solid authority of the bakufu seemed remote and out of touch. Meanwhile, Emperor Go-Daigo rallied dissatisfied warriors seeking to revive imperial power, among them the ambitious Ashikaga Takauji. In 1333, Takauji marched on Kamakura, joined by Nitta Yoshisada from another front. Swift and coordinated, their attack shattered Hōjō resistance. As Kamakura burned, Hōjō Takatoki and his kin ended their lives in tragic ritual. The fall of the Hōjō brought the Kamakura shogunate to an end and ushered in the Kenmu Restoration. Their era of silent regency disappeared into history, leaving behind memories as delicate and brief as falling leaves.

Legacy of the Hōjō Clan

Even after their fall, the Hōjō clan’s legacy resonated through Japanese history. Renowned for imposing order and stability amid turbulence, their governance left an indelible impression on the nation’s political culture. The legal codes they established, such as the Joei Shikimoku, served as blueprints for subsequent regimes. By valuing duty, order, and moral clarity, the Hōjō influenced the evolution of samurai ethics—shaping virtues of simplicity, loyalty, and self-restraint that would define warrior society. Their subtle support for Zen Buddhism deepened its integration into daily life and thought. The Hōjō did not rule with outward show or aggression, but the depth and discipline of their rule became a model for generations to come. Though their time as regents ended, the essence of their governance endures in the fabric of Japanese tradition.