The Age of the Warring States

The Sengoku period began in the mid-15th century, as centralized authority in Japan shattered. The Ashikaga shogunate, weakened by internal discord and unable to assert control, let power slip from its grasp. Local warlords, known as daimyo, seized this opportunity. With ambition and cunning, they carved out territories, established armies, and engaged in relentless conflicts to expand or protect their domains.

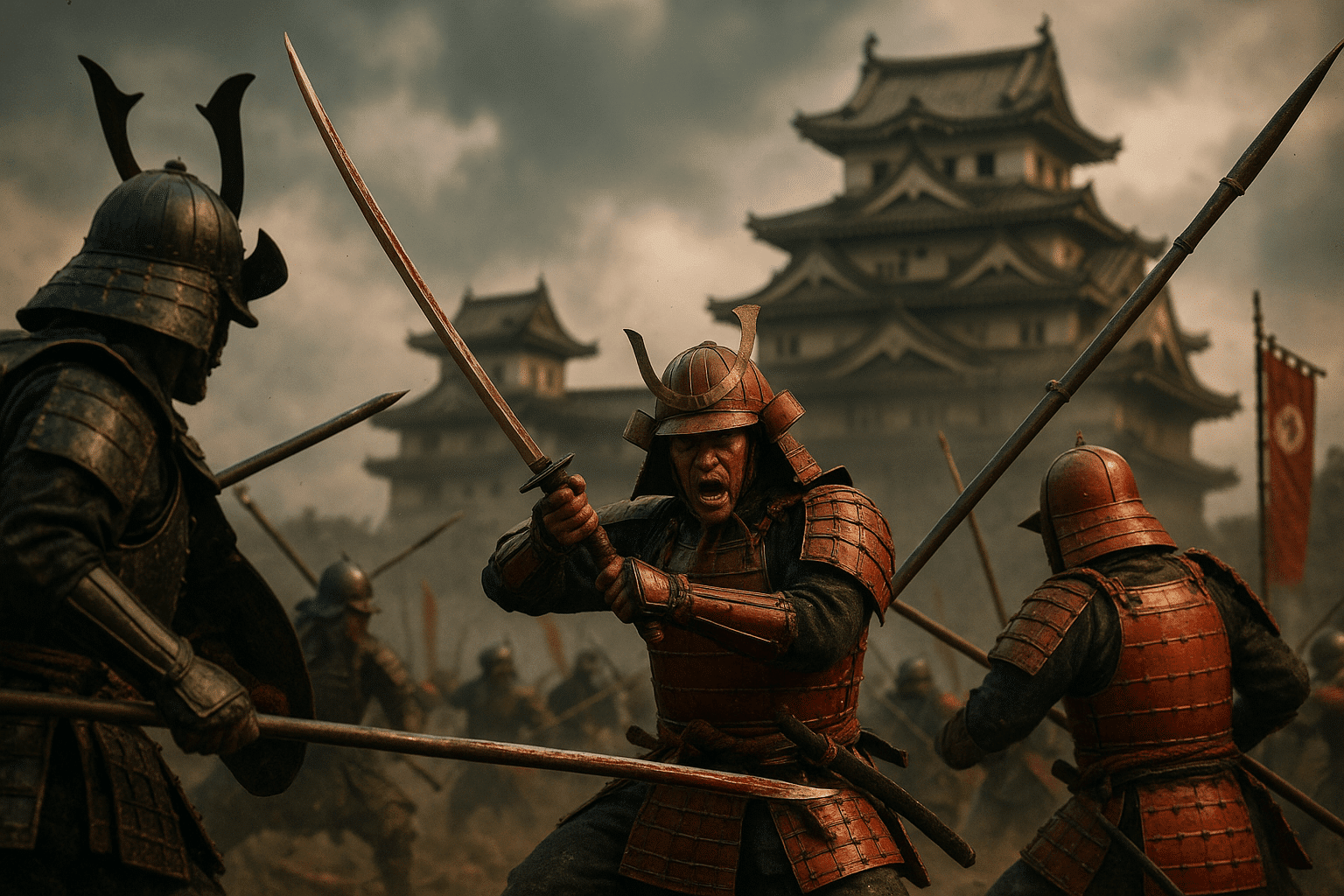

For over a century, Japan was torn by division. New castles crowned hillsides, alliances flowered and withered, and loyalties shifted unpredictably. The samurai’s way became less about ritual and more about day-to-day survival. War was not a rare event—it was the everyday reality.

Yet, amid the chaos, new forms of greatness arose. Military strategy was reimagined, leadership skills sharpened, and the roots of unification began to take hold—watered by ambition and bloodshed. This was the Age of the Warring States: a crucible of conflict, upheaval, and transformative change.

What Drove the Conflict?

The Sengoku Wars erupted from the collapse of the Ashikaga shogunate and the subsequent power vacuum it created. Centralized rule, always fragile, dissolved entirely. Regional lords—the daimyo—rushed to secure and enlarge their holdings.

Japan’s feudal fabric fueled this scramble. Daimyo rallied samurai not in the name of country, but of territory and family legacy. Loyalty was tethered to strength, and honor clung to victory, not title.

No single law or authority unified the land. Weak shoguns lacked ability to command. Local ambition swiftly filled the void left by the central government’s collapse.

Trade and the influx of new weaponry, such as firearms introduced by the Portuguese, shifted advantage to those most adaptable. The balance of power was in constant flux—alliances shifted, and fortunes reversed overnight.

The Sengoku wars were not the result of one man’s ambition nor sparked by one fateful incident; they were the inevitable outcome of a broken system, where ambition thrived in the ruins of order.

Tactics and Terrain

Japan’s rugged landscape—mountains, rivers, and dense forests—played a pivotal role in shaping its warfare. The country’s topology restricted movement to narrow pathways, and whoever controlled these routes wielded real power.

Commanders leveraged terrain to their advantage. Armies followed valleys and ridgelines, making their movements predictable but also vulnerable to ambush. Narrow mountain passes became lethal traps, allowing smaller forces to stall or annihilate their larger foes through surprise and tactical positioning.

Castles were more than fortresses; they were intricately integrated with the land, perched on steep ridges and hills. Their winding approaches, steep ascents, and fortified chokepoints transformed them into formidable defensive positions. Ingenious engineering produced hidden wells, secret doors, and layered defenses to outlast attackers during protracted sieges.

On open ground, formations had to be disciplined and flexible. Samurai led from the front, supported by ashigaru foot soldiers in tight ranks. Every detail—from the slope of the land to the direction of the wind—was considered by strategic commanders. Terrain was never mere background; it often determined the course of victory or defeat.

The Evolving Samurai

Centuries of unending warfare transformed the samurai from ceremonial aristocratic guardians into hardened soldiers, cunning commanders, and innovative strategists—honed and refashioned by conflict.

No longer just icons of honor, samurai became leaders on the battlefield. They learned to study the landscape, plan flanking maneuvers, and lead charges with calculated brilliance. Mastery of the sword remained essential, but now it was joined by the demands of leadership, endurance, and adaptability.

Armor became heavier for protection, while tactics grew ever more sophisticated. Training evolved beyond swordplay, focusing on group coordination, rapid movement, and battlefield communication. Individual valor was now balanced against the discipline of fighting as a unit.

Duty was recast as strategy, and combat as calculation. Through constant warfare, the samurai evolved—from noble retainers to the beating heart of Japan’s military might.

Weapons of War: Swords, Spears, and Guns

The unrelenting conflict of the Sengoku era demanded resilient and effective weaponry. The timeless katana, the versatile spear, and the disruptive firearm each played defining roles on the battlefield.

The katana was more than just a weapon; it was an emblem of the samurai’s soul—its elegant curve and razor edge turning swordsmanship into a deadly art. In skilled hands, a katana could decide a duel before the enemy ever struck.

Spears, or yari, provided reach and advantage, becoming staples for both infantry and cavalry. Armies drilled in disciplined spear formations, creating defensive walls that could blunt enemy charges and protect advancing troops.

The arrival of the gun changed warfare irrevocably. Portuguese traders introduced the tanegashima (matchlock firearm) in the mid-1500s, and the weapon was quickly adopted by forward-thinking warlords such as Oda Nobunaga. Matchlocks redefined combat—slow to reload but powerful enough to pierce armor, they made traditional defenses vulnerable and compelled new tactics.

The sword reflected personal honor, the spear held the line, and the gun upended tradition. Together, these weapons narrate the relentless evolution of warfare during an era defined by survival and innovation.

Decisive Battles and Turning Points

The Sengoku period was marked by pivotal moments—clashes that shaped the future of Japan. Among countless skirmishes, a few battles stand as unmistakable turning points.

The Battle of Okehazama in 1560 was one such moment. Oda Nobunaga, with far fewer troops, launched a bold and unexpected assault during a thunderstorm, catching the mighty Imagawa Yoshimoto unprepared. Nobunaga’s triumph catapulted him to prominence and underscored the era’s new truth: boldness and tactical brilliance outweighed sheer numbers.

The Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 brought an end to centuries of internal conflict. Tokugawa Ieyasu and Ishida Mitsunari led rival factions in a struggle that spanned the entire nation. As the two camps collided and allegiances shifted, Ieyasu emerged victorious. His success consolidated political power and set Japan firmly on the path to lasting unity under the Tokugawa shogunate.

These dramatic confrontations were more than mere battles; they were decisive moments that redirected the course of history, with legacies echoing for generations.

From Chaos to Unification

The Sengoku period was defined by ceaseless warfare and shifting allegiances among regional lords, making lasting peace seem like an unattainable dream. Yet, change finally arrived.

Oda Nobunaga was the first to truly challenge the existing order. Through ruthless efficiency and innovative tactics, he broke the power of formidable rivals and set Japan on a path toward unity. After his assassination, Toyotomi Hideyoshi took up the mantle, managing to bring nearly all of Japan under a single rule, despite lacking a stable system to maintain it.

It was Tokugawa Ieyasu who completed the journey. Methodical and patient, he waited for the opportune moment, striking decisively at Sekigahara. His victory allowed him to claim the shogunate in 1603, heralding the Tokugawa era.

The shogunate established a new, centralized government. Daimyo were pacified, the samurai put under strict regulation, and Japan entered over two centuries of peace and stability. Roads, markets, and administration all became unified under Tokugawa rule. From a nation divided by constant strife, Japan emerged solidified and orderly.

Legacy of the Sengoku Wars

The Sengoku period left a deep and indelible mark on Japan’s history. The end of feudal turmoil made way for the nation’s unification under strong central rule. With Tokugawa Ieyasu’s rise as shogun in 1603, an era of enduring peace and prosperity was born.

Warfare itself was transformed. Castles grew more elaborate and defensible, while the adoption and refinement of firearms forced innovations in strategy and tactics. The samurai’s role also evolved; skill and discipline became as important as valor, aligning with the emerging ideals of bushido—the way of the warrior.

Culturally, the period’s legacy extended beyond the battlefield. The samurai spirit—rooted in loyalty, honor, and ritual—permeated art, literature, and the Japanese sense of identity. Even in times of peace, the lessons carved by war endured.

The fires of the Sengoku wars forged a new Japan: unified, resilient, and forever shaped by the crucible of conflict.