Introduction: An Age of Constant War

From the mid-15th to early 17th century, Japan was enveloped in chaos during the Sengoku period—aptly termed the “Age of Warring States.” The collapse of authority under the Ashikaga shogunate set off a spiral of rivalries and ambition, fracturing the land into countless feudal domains. Each was ruled by its own daimyō, bent on survival and conquest. War raged across open fields and within castle walls, with alliances shifting as quickly as tides. The fabric of society was redefined by the proximity to power, martial ability, and above all, the instinct to survive. Villagers fortified their homes, peasants became warriors, and even those on the social fringes found new roles in the brutal economy of war. In this environment, adaptability was not just valuable—it was essential.

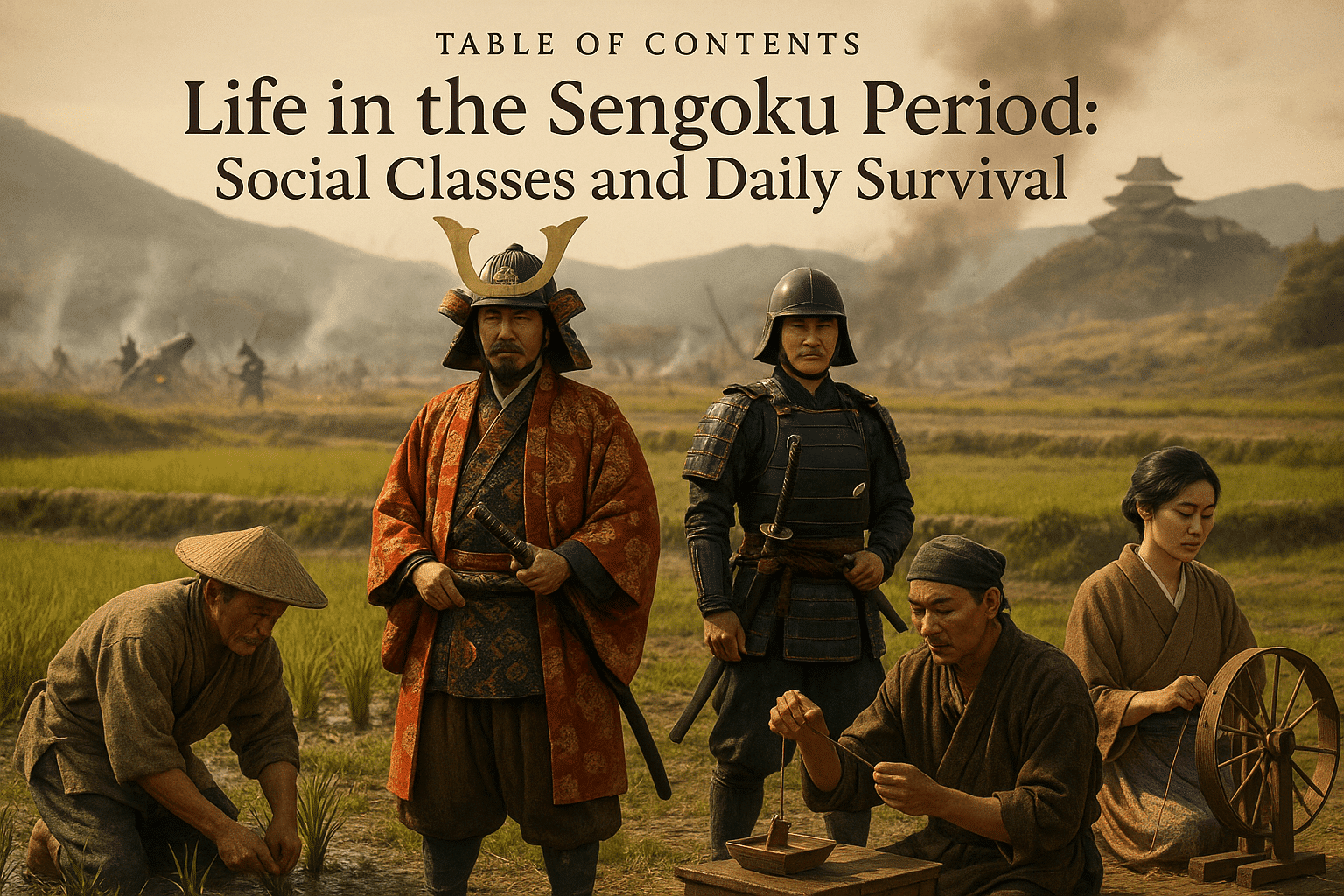

The Ruling Class: Daimyo and Samurai

At the pinnacle of Sengoku society were the daimyo and their loyal samurai. Daimyo were regional warlords, rulers in almost every sense, overseeing both the administration of their lands and the direction of their armies. Protection, governance, and stability of their territories depended on their military strength and ability to forge and maintain strategic alliances. Loyalty was rewarded with land, but treachery and ambition made every bond tentative.

Beneath the daimyo, the samurai enforced their lord’s will. More than warriors, samurai followed bushido—the “way of the warrior”—a demanding code of ethics that emphasized loyalty, courage, and honor above all else. Their dual roles as both military and administrative officials made them the linchpin of governance. In a world where a single betrayal could shift the balance of power overnight, the reputation of both daimyo and samurai was their most valuable asset. Together, they enforced a fragile order, holding their domains with an iron grip amid the nation’s turmoil.

The Farmer’s Burden: Backbone of the Land

While battles determined the fate of lords and warriors, it was the peasants who sustained Japan’s life force. Constituting the vast majority of the population, these men and women tilled the fields and harvested rice—the essential resource feeding both hungry families and marauding armies. Peasant life was defined by grueling labor and a rigid social hierarchy. Bound to the land, they had little freedom to move or improve their circumstances.

Taxation by the daimyō was relentless, often extracting more than half of a peasant’s harvest, regardless of famine or crop failure. Still, obligations to the ruling class remained. The risk of rebellion or dissent was met with swift and brutal punishment. Yet, in spite of these pressures, peasants demonstrated remarkable resilience by forging tightly knit communities, rooted in collective labor and tradition. Their perseverance underpinned the ability of the ruling class to maintain their wars and build their legacies. Though largely unsung, it was their daily toil that truly sustained the Sengoku world.

Merchants and Artisans: Survival Through Skill

Amid the clamor of war, merchants and artisans shaped the practical and economic backbone of society. Denied the privileges of the samurai class, these groups flourished instead through indispensable skill and adaptability. Artisans—blacksmiths, carpenters, armorers, and swordsmiths—became essential for producing weapons, armor, and fortified structures. Their crafts supported not only armies but also the everyday needs of townsfolk and nobles alike. Potters, weavers, and lacquerware makers contributed both practical goods and luxuries that distinguished those in power.

Merchants, officially ranked beneath peasants, carved out crucial roles by supplying armies, facilitating trade, and negotiating safe passage in exchange for profit and protection. Towns sprang up around castles and at crossroads, their marketplaces transforming into vital centers of commerce and information. By becoming indispensable not through might, but through shrewd negotiation and service, merchants and artisans quietly shaped the prospects of whole communities, demonstrating the power of skill and tenacity in the face of upheaval.

Women’s Lives: Shadows in the Stronghold

The story of Sengoku Japan is often told through the exploits of men, but women’s influence silently permeated all levels of society. Among the elite, noblewomen secured alliances through arranged marriages and managed estates during their husbands’ absences. Some received martial training to defend their homes if conflict reached their doorsteps. Despite these flashes of agency, most noblewomen’s power was mediated through family and duty, rather than personal freedom.

For peasant women, life was laborious and unrelenting. Alongside men, they worked the fields, maintained households, and ensured their families’ survival—an especially challenging task when left alone by conflict or loss. Their resilience was essential, keeping the rhythms of daily life intact amid uncertainty. Although rarely chronicled in official records, the resourcefulness of Sengoku women helped hold together the fragile fabric of their communities, proving that real strength could lie in the unseen and uncelebrated.

Faith, Folklore, and Fear

In a world wracked by constant warfare and the everyday threat of famine, faith became a vital anchor. Buddhism, particularly the Pure Land and Zen sects, offered hope and refuge for those in distress. Temples doubled as centers of learning, political activity, and sanctuary, imbuing them with influence beyond the spiritual realm. Shinto, Japan’s indigenous belief system, helped people interpret natural disasters, war, and loss, with villagers routinely seeking blessings from local kami for protection and prosperity.

Folklore thrived in this climate of uncertainty, where tales of yōkai, vengeful spirits, and protective deities provided both cautionary lessons and comfort. These stories were woven into daily life, guiding behavior and offering explanations for misfortune. In effect, religion and folklore together equipped people with a spiritual armor against the relentless instability—creating shared narratives that helped communities endure and make sense of their fractured world.

Conclusion: Order Within Chaos

Beneath the storms of war and shifting loyalties, Sengoku Japan was sustained by a deep but often invisible order. Samurai and daimyo enforced strict codes of honor and hierarchy, peasants fed the nation, artisans and merchants adapted to every turn of fortune, while women and faith quietly kept the home and the spirit alive. Temples, shrines, festivals, and the routines of rural and urban communities continued, creating stability where little existed.

Survival in this turbulent age demanded flexibility, solidarity, and a tenacious sense of duty. The Sengoku period stands as a testament not just to conflict, but to the remarkable endurance of its people and their capacity to forge meaning and community amidst chaos. In that delicate balance between upheaval and continuity lies the true essence of the era—a model of resilience shaped by adversity, and the enduring strength of social bonds.