Introduction to Hamon

The hamon is one of the most visually captivating features of a traditional Japanese sword. It refers to the distinctive temper line that runs along the edge of the blade, created during the differential hardening process. This effect isn’t merely decorative—it’s a manifestation of meticulous craftsmanship, where the blade’s edge is hardened for cutting performance while the spine remains softer for flexibility.

Originally developed as a practical technique to enhance the sword’s durability and effectiveness in battle, the hamon also evolved into an art form. Swordsmiths began to refine and personalize their methods, producing unique patterns that became signatures of their work and schools of forging. These temper lines range from subtle and wave-like to bold, complex designs—each telling a story of tradition, technique, and aesthetic philosophy.

Understanding the hamon offers valuable insight into the soul of the Japanese sword, bridging functionality with artistry and preserving centuries-old techniques passed down through generations.

Purpose of the Hamon

The hamon, the visible temper line on a Japanese sword, embodies both function and beauty—making it one of the most revered elements in traditional sword-making.

Functionally, the hamon results from a process called differential hardening. This technique involves applying a clay mixture to the blade before heating and quenching. The edge, coated thinly or left bare, cools rapidly, becoming extremely hard to retain a sharp cutting edge. In contrast, the spine, covered with a thicker clay layer, cools more slowly, remaining softer and more flexible. This duality gives the sword remarkable resilience—hard enough to cut effectively, yet pliant enough to absorb shock without breaking.

Aesthetically, the hamon is celebrated as a unique signature of each swordsmith’s artistry. The patterns that emerge—from waves and clouds to flames and mountains—are not just artifacts of function but expressions of individuality and tradition. No two hamon are exactly alike, their subtle lines and shapes reflecting the smith’s skill, creativity, and dedication to their craft. Collectors and martial artists alike admire the hamon both as a marker of quality and as a testament to centuries of Japanese sword-making heritage.

Suguha – The Straight Path

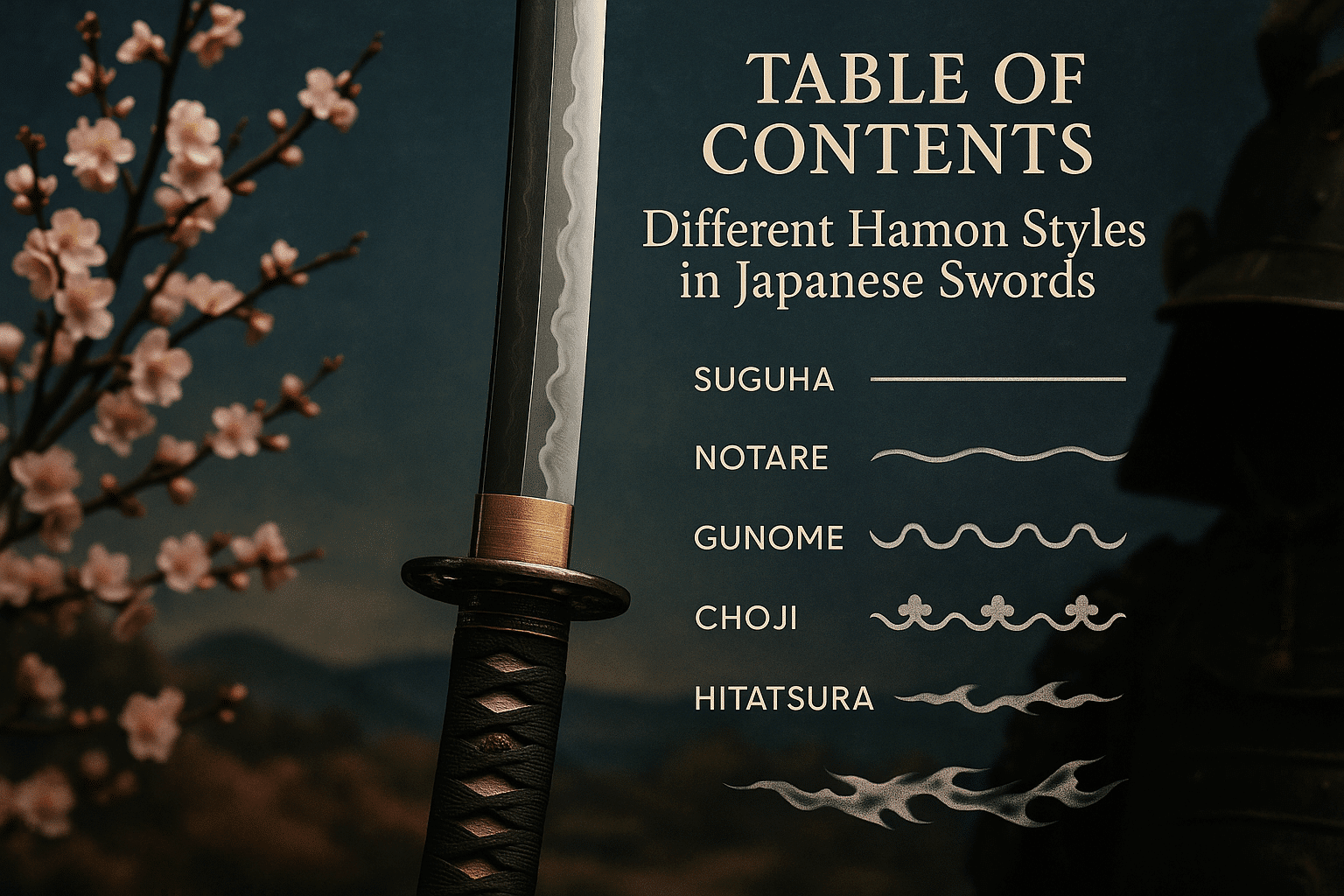

The suguha hamon, characterized by its straight, unbroken line along the edge of the blade, is one of the most understated yet revered patterns in traditional Japanese swordsmithing. Unlike the more elaborate midare or choji styles, suguha emphasizes minimalism and precision. Its clean geometry reflects not just technical mastery, but also a philosophical adherence to simplicity and clarity.

This style emerged prominently during the Heian and Kamakura periods, particularly in swords forged by the Yamashiro and Yamato schools. Suguha’s elegant restraint was favored by warriors who valued function as much as form. Because it requires exceptional skill to execute such straight, consistent patterns—without the forgivable distractions of a more irregular hamon—suguha is often seen as a testament to a smith’s refined technique.

Visually, suguha hamon delivers a sense of calm and balance. When polished properly, the line appears crisp and luminous, subtly highlighting the blade’s edge without flamboyance. It’s a pattern that speaks quietly but with authority, making it a favorite among collectors and practitioners who appreciate traditional aesthetics and the disciplined craftsmanship behind them.

Notare – The Wavelike Flow

Among the many hamon styles that grace the blades of traditional Japanese swords, notare stands out for its graceful elegance. Characterized by gentle, wavelike undulations along the edge, the notare hamon embodies a sense of continuous flow and refined artistry. Unlike the more rigid or complex patterns found in other styles, notare’s soft curves suggest calm motion—like ripples on a quiet pond—offering both aesthetic balance and metaphorical depth.

This style was particularly favored by swordsmiths of the late Kamakura and Muromachi periods, who sought a harmonious blend of strength and subtle beauty. The natural ebb and flow of the notare hamon reflect not only technical mastery but also a philosophical appreciation for the impermanence and rhythm of life, deeply rooted in Japanese culture.

Notare hamon is often found on tachi and katana made by the schools of Bizen and Soshu traditions, where the style’s flowing lines complemented the curvature of the swords themselves. To this day, collectors and practitioners appreciate notare for its timeless, fluid aesthetic that speaks to both the sword’s functionality and its soul.

Gunome – The War Pattern

Gunome, often referred to as the “war pattern,” is one of the most recognizable and dynamic hamon styles in Japanese swordsmithing. Characterized by a rhythmic series of rounded, semicircular peaks along the blade edge, gunome evokes the image of rolling waves or the teeth of a comb—both symbols of controlled power and continuity. This repeating, symmetrical pattern was not merely decorative; it underscored the blade’s martial purpose.

Traditionally favored by warrior clans and battlefield commanders, the gunome hamon was seen as a mark of resilience and cutting efficiency. The uniformity of the pattern allowed for consistent strength along the edge, helping swords absorb impact while maintaining a sharp, reliable bite. Some variations blend gunome with other styles, such as choji or notare, adding complexity without sacrificing the strong visual identity of the base pattern.

Whether in early koto era swords or more refined shinto and shinshinto blades, gunome hamon reflects a balance between artistry and wartime utility—fitting for a pattern steeped in a warrior’s heritage.

Choji – The Clove Blossom

One of the most visually striking and artistically admired hamon styles is the choji, or “clove blossom” pattern. Named for its resemblance to the rounded, petal-like shape of opened clove buds, choji hamon features a repeating series of curved peaks and valleys that ripple along the blade’s edge in a wave-like formation. These undulations can vary in height and width, creating a dynamic rhythm that gives the sword both elegance and individuality.

The choji style became particularly prominent during the Kamakura period and is often associated with the Bizen tradition, especially among renowned smiths like Osafune Nagamitsu. Its intricate design not only highlights the smith’s technical mastery but also reflects a balanced harmony between function and form—the peaks align with hardened areas, offering both beauty and performance.

There are many variations of choji, including gunome-choji (a mix of semi-circular and clove-like forms) and oshi-choji (where the clove shapes are densely packed), each requiring immense precision in temperature control and clay application during the differential hardening process. A well-executed choji hamon creates a captivating visual flow, often enhanced under proper lighting, making it a favorite among collectors and connoisseurs who appreciate both swordsmithing skill and aesthetic subtlety.

Hitatsura – The Full Body Flame

Hitatsura, meaning “full temper” in Japanese, is one of the most visually arresting hamon styles found on traditional Japanese swords. Unlike more linear or restrained temper lines, hitatsura covers the entire surface of the blade—both the edge and the body—with a chaotic, almost explosive pattern of hardened steel. This effect creates the impression of flames licking across the metal, earning it the poetic nickname “the full body flame.”

This style became especially popular during the Muromachi period and is strongly associated with the Soshu tradition, particularly the master swordsmith Sengo Muramasa. The dramatic aesthetic was not just for show—it often indicated a powerful quenching process and suggested a hardened, war-ready blade.

Crafting a hitatsura hamon requires remarkable skill and control. During the differential hardening process, smiths apply clay in varying thicknesses not just along the edge, but across the entire blade. When quenched, this results in both the standard hamon at the edge and a field of hardened spots, called tobiyaki, and ashi, that dance across the surface like sparks from a fire.

Collectors and martial artists alike seek out hitatsura blades not only for their striking appearance, but also for the technical mastery they represent. When gazing upon the full body flame, you’re looking at more than a pattern—you’re witnessing fire captured in steel.

Conclusion: Reflection in Steel

The hamon is far more than just a line etched in steel—it’s a signature, a philosophy, and a silent story told through fire, steel, and unwavering craftsmanship. Each style, from the wild undulations of midare to the disciplined elegance of suguha, reveals the soul of its maker and the practical demands of battle. What begins as a technical necessity for hardening ends as a timeless expression of beauty. Through the myriad forms of hamon, we glimpse the incredible balance Japanese swordsmiths achieve between artistry and function. In every blade, in every curve and notch of tempering, the spirit of the sword is etched, bearing testament to centuries of tradition and the enduring pursuit of perfection in steel.